Design is a mirror of culture, history, and innovation. Each major movement reflects its era, pushing boundaries and redefining aesthetics and functionality. From the disciplined forms of Bauhaus to the raw, unapologetic nature of Brutalism, the evolution of design is a story of creativity finding its voice. Let’s explore how these movements shaped modern design and continue to influence our work today.

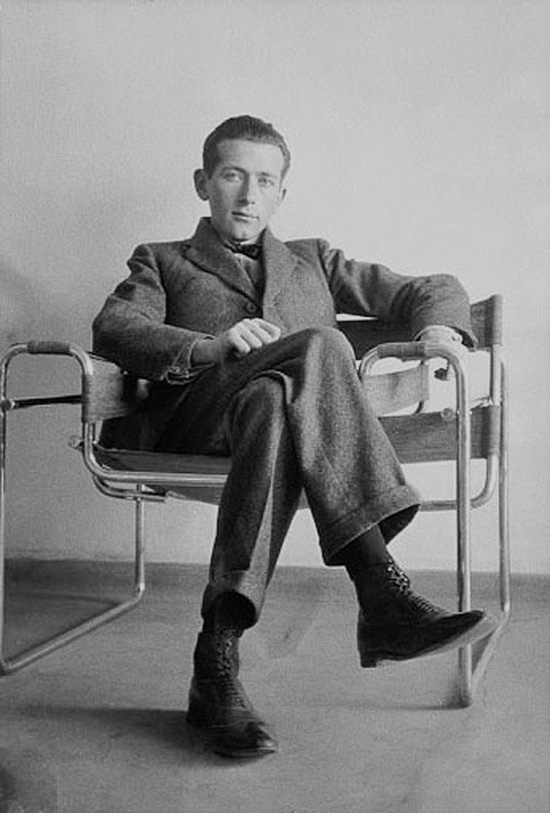

It all began with Bauhaus, the revolutionary school of design founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany. At its core was the belief that art and craftsmanship should unite, creating works that were as functional as they were beautiful. Bauhaus designs discarded the ornate in favour of simplicity—clean lines, geometric forms, and purpose-driven aesthetics. Think of Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair, a minimalist masterpiece of tubular steel, or Josef Albers’ type experiments, which emphasised clarity over flourish. As Gropius succinctly put it, “Form follows function.”

The Bauhaus redefined design as a harmonious union of function and aesthetics, a principle that remains foundational in modern design practice.”

The Bauhaus redefined design as a harmonious union of function and aesthetics, a principle that remains foundational in modern design practice.”

Marcel Breuer sitting on the Wassily Chair (ca. 1926)

Marcel Breuer sitting on the Wassily Chair (ca. 1926)

What made Bauhaus truly groundbreaking, however, was its impact beyond furniture and architecture. It redefined visual communication. Typography became not just a tool for delivering information but an art form in itself. This stripped-back philosophy resonates today, particularly in digital interfaces, where usability is king. Every intuitive navigation bar and clean sans-serif typeface owes something to the Bauhaus ethos.

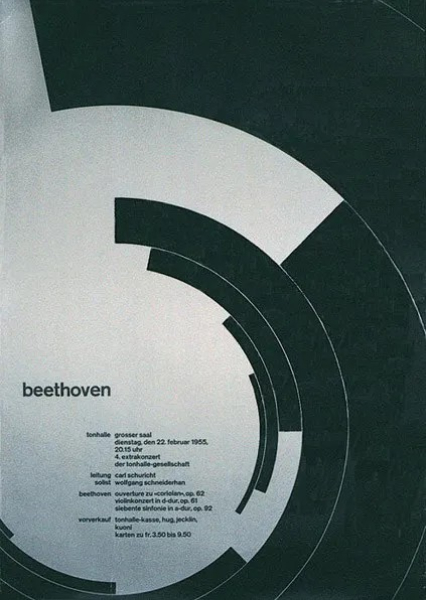

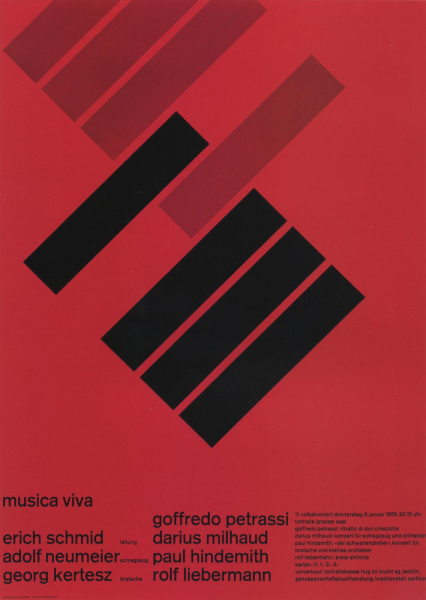

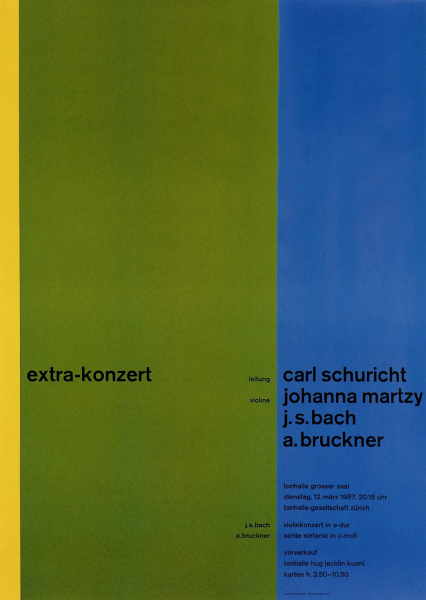

After the disruption of World War II, the world craved order and stability—and design responded with the emergence of the Swiss Style, or International Typographic Style. Influenced by Bauhaus but with a stricter emphasis on grids and alignment, this movement championed precision and clarity. Josef Müller-Brockmann became one of its leading figures, with his posters—like the celebrated Beethoven Poster—embodying balance, neutrality, and legibility.

Josef Müller-Brockmann – from left to right: Beethoven (1955), Musica-Viva (1958) & Concert (1958)

Swiss Style wasn’t just about aesthetic tidiness; it was a philosophy of communication. The grid systems it popularised became blueprints for everything from print layouts to modern-day web design. Helvetica, designed during this era, remains a designer’s go-to typeface, thanks to its clean neutrality. In essence, the Swiss Style provided the backbone for today’s minimalist design principles.

As the mid-20th century progressed, optimism crept back into the cultural narrative, and design became more playful. Mid-century modern design, which bridged Bauhaus minimalism and human-centred joy, produced iconic works that married form and function. Charles and Ray Eames epitomised this movement with designs that were innovative yet accessible. In the world of graphic design, Paul Rand applied modernist principles to corporate branding, revolutionising how companies presented themselves. Rand’s work, such as his logos for IBM and ABC, proved that design wasn’t just about looking good—it was about creating an identity. As he famously said, “Design is the silent ambassador of your brand.”

Charles and Ray Eames married in 1941, and worked together for the next 37 years. (Credit- Eames Office LLC)

These principles of clarity and identity found their way into the rapidly developing field of digital design. Branding today owes a significant debt to mid-century modernism, where a logo must function effectively whether on a billboard or a mobile app icon. The simplicity of Rand’s logos echoes in the clean, scalable marks that define today’s visual identities.

And then, there’s Brutalism. The polar opposite of polished modernism, Brutalism revelled in rawness and honesty. Originally an architectural movement defined by harsh concrete structures and utilitarian aesthetics, it found unexpected relevance in digital design decades later.

Brutalism challenged the polished veneer of design, favouring raw, unapologetic functionality over perfection—a bold statement in any era.”

Web Brutalism emerged as a reaction against overly slick, templated sites, embracing stripped-down, intentionally “ugly” designs. These sites eschew gradients and glossy buttons for stark layouts and functional starkness. What might seem jarring at first glance is, in fact, a rebellion against homogenisation—a reminder that design isn’t just about following trends; it’s about breaking rules.

Despite its divisive nature, Brutalism makes an important point: design doesn’t always need to please. Sometimes, it’s meant to challenge, provoke, or simply function without pretense. In this sense, the spirit of Brutalism keeps alive the radical experimentation of Bauhaus, even if its aesthetic couldn’t be more different.

Today’s digital design owes its precision to Swiss grids, its ingenuity to the Bauhaus, and its daring creativity to the Brutalist ethos.”

These movements—Bauhaus, Swiss Style, Mid-century Modern, and Brutalism—may seem like historical artefacts, but they are the foundation upon which modern design is built. The grid systems of Swiss Style underpin every responsive website, while Bauhaus’s principle of functional beauty informs the minimalist interfaces we use every day. Brutalism, though niche, reminds us to question conformity, and mid-century modernism proves that practicality and delight can coexist.

As designers, we are the inheritors of these legacies. Every decision we make, whether choosing a typeface or crafting a user flow, carries echoes of Gropius, Tschichold, Rand, and their contemporaries. Design evolves, but it never truly forgets its roots.

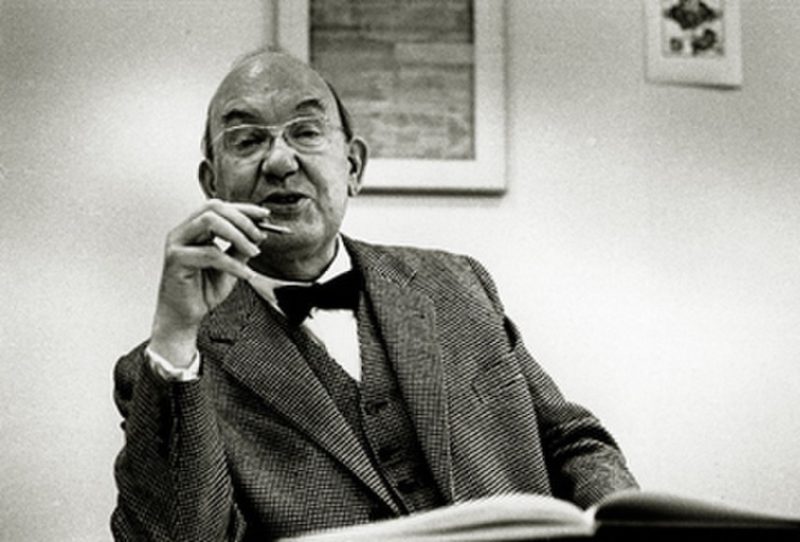

To paraphrase Jan Tschichold, the pioneer of modern typography: “Perfect typography is certainly the most elusive of all arts.” In the same way, perfect design is a moving target, shaped by the movements of the past but forever reaching toward the future.

Jan Tschichold in a photograph in Locarno by Erling Mandelmann 1962

Resources

The New Typography by Jan Tschichold

This classic manifesto outlines Tschichold’s revolutionary approach to typography and layout design, with an emphasis on functional, modern aesthetics.The ABCs of Bauhaus: The Bauhaus and Design Theory by Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller

A concise and visually rich introduction to the principles of Bauhaus, covering how its philosophy shaped modern design.Grid Systems in Graphic Design by Josef Müller-Brockmann

An essential guide to understanding and implementing grids in design. This book is the cornerstone for any designer interested in Swiss Style principles.Paul Rand: A Designer’s Art by Paul Rand

A collection of essays and insights from one of the most influential graphic designers of the 20th century, exploring the relationship between creativity and business.B is for Bauhaus: An A–Z of the Modern World by Deyan Sudjic

A thought-provoking exploration of modern design movements, including Bauhaus, with reflections on their lasting impact on design culture.

0 Comments