Midcentury modern design tends to conjure images of Eames chairs perched artfully in minimalist lofts, teak credenzas against white brick walls, and the occasional sunburst clock—usually curated to signal that you, yes you, have taste. But beyond the Instagrammable surfaces and the enduring market for retro furniture, this movement was rooted in a radical rethinking of how form and function could coexist, democratize good design, and, in many ways, prefigure today’s user-centred design philosophy.

At its core, midcentury modern wasn’t merely an aesthetic trend. It was an attempt to reconcile the rapid technological shifts of the early 20th century with a human need for clarity, usability, and beauty. Designers like Charles and Ray Eames weren’t setting out to create museum pieces; they were trying to make products that improved everyday life. Their legendary Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman—iconic to the point of cliché—was, in their own words, designed to be “a special refuge from the strains of modern living.” It was ergonomics before ergonomics was a buzzword. It was form that didn’t just follow function—it cajoled it into something delightful.

Beyond the Eames duo, a constellation of visionary designers championed this functionalist ethos, each leaving an indelible mark with their distinct approach.

Eero Saarinen. Seated at drafting table. Cranbrook Archives, Saarinen Family Papers

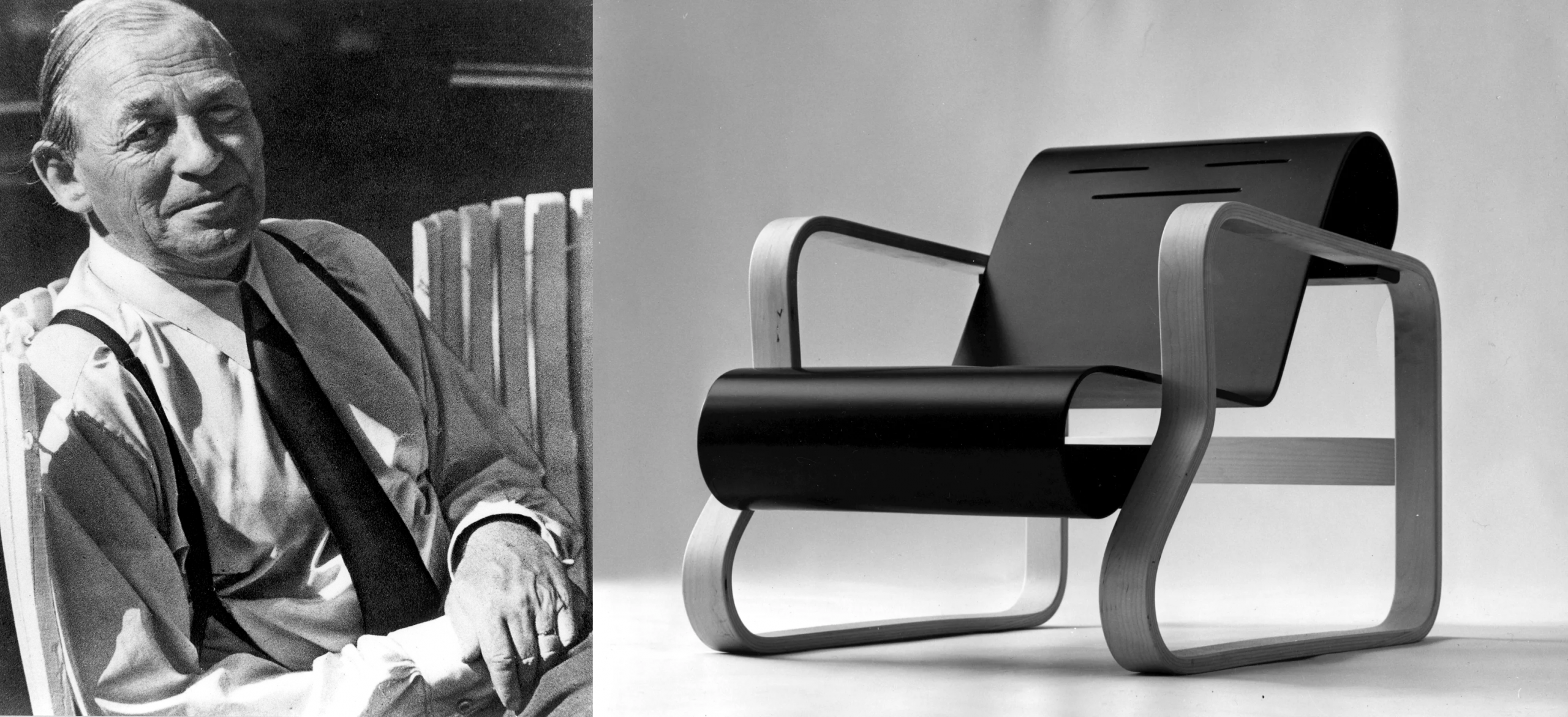

Alvar Aalto, the Finnish architect and designer, exemplified a “gentle modernism” that blended clean lines with organic forms and a deep respect for natural materials. His Paimio Chair (1933), designed for a tuberculosis sanatorium, wasn’t just visually striking; its gentle curves were specifically engineered to help patients breathe more easily. Similarly, his ubiquitous Stool 60 (1933), crafted from bent plywood, showcased a groundbreaking lamination technique that made it incredibly sturdy, stackable, and adaptable, proving that mass production could still embody warmth and human sensibility. Aalto’s work underscored that functionality could extend to the psychological and physical well-being of the user.

Another Finnish-American master, Eero Saarinen, was renowned for his sculptural and fluid forms that sought to solve specific design problems. His iconic Tulip Chair and Table series (1956), designed for Knoll, was a direct response to what he called “the slum of legs” under dining tables. By consolidating multiple legs into a single, elegant pedestal, Saarinen created a visually uncluttered space that remains remarkably functional and aesthetically pleasing. His Womb Chair (1948), also for Knoll, was conceived at the request of Florence Knoll, who desired a chair she could “curl up in.” Its enveloping, comfortable form, achieved through innovative fiberglass moulding, perfectly embodies the idea of creating a supportive refuge.

As Charles Eames put it, ‘Design is a plan for arranging elements in such a way as best to accomplish a particular purpose.’ The purpose, in the end, is always human.

Danish architect and designer Arne Jacobsen epitomized the refined simplicity of Scandinavian modernism. His Egg Chair (1958) and Swan Chair (1958), designed for the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, were not just luxurious statement pieces but integral parts of a “total design” concept for the hotel. The Egg Chair’s high, enveloping back provided a sense of privacy and intimacy in a public lobby, while its innovative use of a strong foam inner shell allowed for its distinctive sculptural form and comfort. His Series 7 chair (1955), a development of his earlier “Ant” chair, showcases his mastery of pressure-moulded veneer to create a lightweight, stackable, and highly versatile chair that has become one of the most sold chairs in history, a testament to its practical elegance.

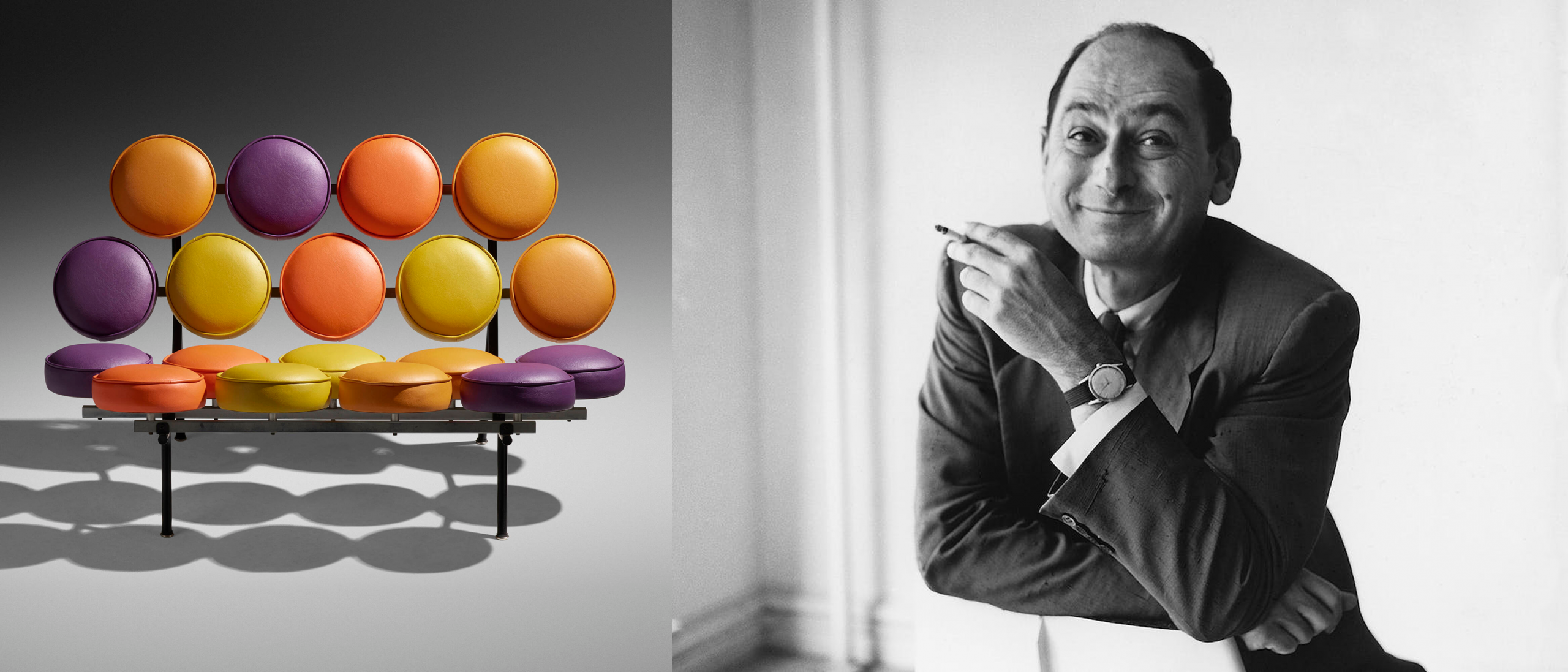

George Nelson, an American designer and the design director for Herman Miller, was a prolific innovator who pushed the boundaries of functional design with a touch of playful ingenuity. His Marshmallow Sofa (1956), though visually whimsical, was an experimental attempt at modularity, constructed from individual circular cushions, offering flexibility in arrangement. The Ball Clock (1949), one of his most recognizable designs, re-envisioned the traditional clock face, making time-telling clear and engaging through simple, colourful spheres, emphasizing legibility and playful interaction. Nelson also pioneered the concept of modular office systems, like his Executive Office Group (1947), which anticipated the need for adaptable and efficient workspaces long before open-plan offices became commonplace.

Arne Jacobsen + The Swan and The Egg chairs(1958)

he contributions of these designers, alongside others like Florence Knoll, who systematized modern office interiors and created timeless, understated furniture like her Lounge Collection (1954), and Isamu Noguchi, whose Akari light sculptures (1951) brought a poetic, diffused light into homes while being ingeniously collapsible for flat-pack shipping, reinforce the underlying principle.

Dieter Rams, whose work at Braun distilled the principles of simplicity and clarity into every product, was similarly motivated by the conviction that good design should be honest, unobtrusive, and understandable. His Ten Principles of Good Design read like a manifesto for user-centred design decades before UX became a discipline. Rams believed that “good design is as little design as possible.” Not because designers should abdicate their role, but because restraint created space for the user to feel in control. The Braun SK4 radio, with its transparent Plexiglas lid and intuitive dials, offered a tactile experience that made technology approachable rather than intimidating. It invited interaction—an early nod to the kind of user agency we now prize in digital products.

Alvar Aalto + Armchair 41 _Paimio_ chair, black lacquer (1932)

It’s tempting to view midcentury modern as frozen in time, a relic of postwar optimism, but its DNA is alive and well. Think about the crisp simplicity of Apple’s hardware design—a lineage directly traceable to Rams’ influence on Jony Ive. When you hold an iPhone, you’re not just holding a piece of technology; you’re holding the distilled ideas of 20th-century designers who believed that mass production needn’t mean soulless products. This convergence of utility and beauty is precisely why the movement has proven so stubbornly relevant.

But it wasn’t all smooth lines and utopian ideals. Midcentury modern design sometimes struggled to balance ambition with accessibility. The push to create clean, rational environments occasionally veered into sterile territory, alienating those who preferred a richer sensory experience. For every Eames Lounge that aged gracefully into a beloved heirloom, there was a plywood side table that looked tired and flimsy within a few years. This tension between durability and disposability is a lesson for contemporary designers: simplicity must be grounded in context and empathy, not merely a visual strategy.

What can today’s designers learn from this era beyond the obvious aesthetic cues? For one, the idea that design thinking must account for how objects—or digital interfaces—fit seamlessly into people’s routines. When a product requires elaborate instruction manuals, it often signals a failure of empathy. Midcentury designers recognized that users were not an afterthought to be coaxed into compliance; they were collaborators whose needs, habits, and aspirations shaped the final product. It’s a lesson worth reasserting in an age of increasingly complex technology.

Dieter Rams…believed that ‘good design is as little design as possible.’

Consider the example of designing a mobile banking app. It’s easy to fall into the trap of loading it with every conceivable feature—investment tracking, budgeting tools, peer-to-peer payments—while burying the simple act of checking your balance behind multiple layers of navigation. Rams’ maxim that “good design is thorough down to the last detail” is particularly apt here. If the primary function isn’t obvious or effortless, no amount of minimalist styling can redeem the experience. Function without friction is still the ultimate goal.

In the realm of graphic design, midcentury modern also left a profound mark. Josef Müller-Brockmann, with his rational Swiss grid systems, demonstrated that clarity wasn’t just a matter of taste; it was a moral imperative. His posters for the Zurich Tonhalle Concerts distilled information into harmonious compositions that respected the viewer’s time and intelligence. These visual frameworks were forerunners of today’s responsive layouts and modular design systems. The grid—once a revolutionary tool for print—has migrated seamlessly into digital environments, guiding how we create flexible, user-friendly experiences.

George Nelson, 1957. Photo by Arnold Newman + Marshmallow Sofa (1956)

The future, of course, will introduce challenges that even the most visionary midcentury designers couldn’t have predicted: AI-generated interfaces, virtual reality spaces, and the ever-shifting landscape of ethical design. Yet the spirit of midcentury modern offers a compass. If we begin each project by asking not “How can this look more modern?” but rather “How can this better serve the person using it?” we’re more likely to arrive at solutions that transcend trends. As Charles Eames put it, “Design is a plan for arranging elements in such a way as best to accomplish a particular purpose.” The purpose, in the end, is always human.

So next time you admire a piece of midcentury furniture or a sleek interface, look beyond the surface polish. Ask yourself what it means to make something honest, approachable, and—yes—beautiful, without ever losing sight of why it exists in the first place. In a world saturated with visual noise, perhaps the most radical thing a designer can do is to create something quietly, persistently functional.

Florence Knoll in her role as the leader of the Knoll Planning Unit, circa 1955

Resources

Eames: Beautiful Details by Charles and Ray Eames

A visually rich exploration of the Eames’ work.

Grid Systems in Graphic Design by Josef Müller-Brockmann

The definitive guide to clarity and order in visual communication.

Designing Design by Kenya Hara

Reflections on the role of design in shaping culture and behaviour.

Less and More: The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams by Klaus Klemp and Keiko Ueki-Polet

A detailed examination of Rams’ legacy and its relevance today.

0 Comments